As mostly rational, fairly successful adults, most of us lucky enough to still have living parents hope that family dynamics during visits will be enjoyable, connective, potentially heart-warming experiences, at least in part. It seems though from my personal and professional experience that success in this, at least when in close proximity, is alarmingly rare.

It can be surprising each time, if you’re anything like me, to experience intense reactivity, and to feel like a child again in the presence of your parents. Oh Lord, I say, can’t I get beyond this? Come on already. I’ve done some inner work, I realise xyz, and now I want to be an adult and have an adult relationship. So I’m still learning I guess. Here I share some of what I’ve learnt. If you too have not yet found the place of Zen when with your Family of Origin, this is for you.

n.b. Since I don’t yet have adult children to find challenging, I write this from the adult child’s perspective. I should really interview my parents to bring a more rounded approach. Maybe in a sequel. Or a next life. Or give me 20 years and I’ll write it myself!

What’s going on? Why do I get so reactive?

Each person and each family system is different of course, but here are some factors that might be relevant;

- Old wounds can still be sore. Difficult memories are held in our emotional (or limbic) brain. Unless we’ve done some healing (involving more than knowing and understanding the story) the old hurts may still be there, like it or not.

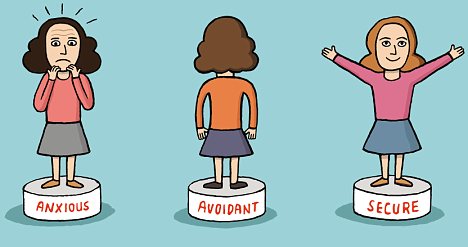

- Our style of attachment with each parent (see my post on Attachment style). Our attachment style will likely still be the same as when we were young.

- Each generation has different values and expectations. Each generation tends to challenge and react to the previous ones’ values. Neither is likely to change it’s deeply held value because of the other offering their perspective!

- Aging. Your parent is likely going through their own aging process, whether they are fighting it, ignoring it or embracing it. Aging in our society of anti-aging, is often not an easy process. They have their own experience and their own reasons. They may have different priorities now. They may not be how you want them to be, or want what you want them to want.

Some things I have learnt:

-

We have 3 mothers and 3 fathers

- The mother and father we had

- The mother and father we wish we had

- The mother and father we currently have

At any moment all 3 characters can be present in our reactions.

For example, (A) if our parent criticised us in some way regularly when we were young, there may be left over hurt from that and a response, like a “hiding inside” feeling for example. At the same time, (B) we may have longed for a relaxed, easy going parent with whom we could settle in with and be ourselves – so there will be a longing for that and likely a frustration that it’s not a reality. And then the reality of the changed parent we see before us, likely aging or at least maturing, perhaps retired, with their own emotional responses to their transitions and their own hopes and fears of us and our children if we have them. We may have our own response to their situation (C) – perhaps wanting more/different for them, wishing they were a different character, not wanting them to be in pain, wanting them to accept help etc.

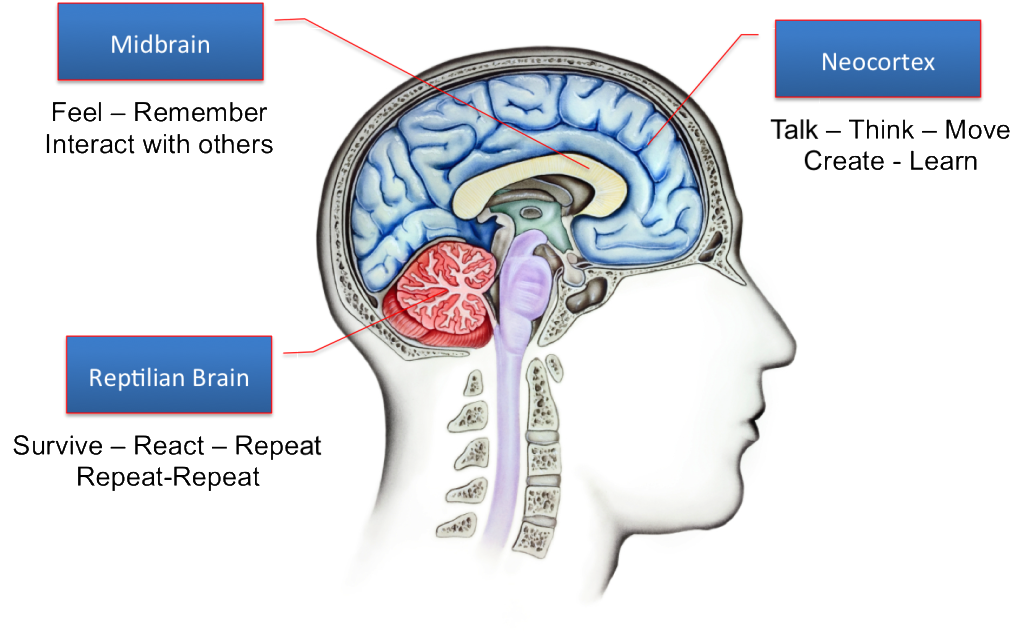

2. Our limbic brain remembers

Difficult emotional experiences have been shown to be lodged in the midbrain in the limbic system. This limbic area is linked to the brain stem and together they seem to regulate the Fight/Flight/Freeze response. For more on the brain see Dan Siegel’s work (particularly I like his hand map of brain-video).

Basically if we perceive a present-day threat in a family dynamic (which may be as simple as a familiar feeling of how we felt trapped/threatened/etc as a child), our limbic and reptilian systems may go into “emergency mode” to prepare us as if there was a life/death threat. We may feel our heart beat more, a tight chest, blood rush to our limbs (Fight/Flight)… or feel shut down and frozen (Freeze). All this doesn’t help our adult selves respond in a civilised way. Our neotcortex thinking function in this situation effectively shuts down (again see Siegels’ hand model of brain). See below (#4) for ideas of how to calm your limbic brain.

What can I do?

If you’ve had a challenging relationship with one or both of your parents, don’t expect it to be different. Expecting otherwise is living with the idealised parent in the forefront and may set up up for failure. Prepare for it to be the same AND know what you can do differently.

1. Plan a visit that respects your own boundaries

For example stay in a separate place, have your own transportation, just go for dinner not for the weekend. If sensing and setting your boundaries is challenging, practice and notice what your tendencies are and whether they are working for you. Take this opportunity to do some work on your ability to stand up for yourself. Even baby steps are steps.

2. Have an alternative plan, a way out

Even if you don’t use it, your limbic system will settle better if it knows it’s not stuck in a situation, like it may have been as a child. So have a place to go if things go sour even if it’s a motel.

Have people to visit or be close to who you like and who like you. This could mean sitting next to your brother at a potentially stressful dinner, or planning a visit with Aunt Allie, or having your old high school friend on text standby so you can go to her house if things get too much.

Know places to go where you are comfortable and have a good time.

Remind yourself it’s not like it was as a child – you have more agency now, you can choose how to response, you can choose to leave.

4. Yes AND

If a parent will likely ask something that you feel pushes your boundaries in some way, practice your response. For example “So I hear you asking/saying…. [repeat essence of what they asked/said] and I can see why you’d want me to do that/why you’d think that… AND what I can do is/what I ask for is….”.

Some of the time you can choose to do it there way, but if something really isn’t possible for you, say what you can do instead.

5. If you get “flooded” self-soothe your limbic system

Couples therapist John Gottman says it takes 20 minutes to calm the physiological arousal system once it’s started. Here are guidelines (taken from John Gottman couples work).

6. Accept and be kind towards your experience

The “5 A’s”Taken from David Richo’s book How to Be an Adult in Relationships Attention: notice your experience (i.e. “tight chest”, anger, wanting to hide) Acceptance: accept that these reactions are there for a reason, and it’s okay Appreciate: your reactions likely kept you safe and were useful at earlier points in your life. Allowance: allow the feelings and reactions to be there. Don’t try to make it different. Affection: be kind towards the feelings, to your reactions, to the situation perhaps. |

7. Plan for success

What situations do you best connect with your parents? Try to set up some of those circumstance.