Are you curious about your patterns in your intimate relationships? If you are in a relationship, does your partner want you to be more open or soft and you just don’t know how? Do you keep obsessing over your partners’ behaviour or whereabouts and want to let it go? So… what do you think your attachment style is?

Attachment theory is a useful lens for understanding your long standing tendencies in intimate relationships. Understanding your attachment style is the first step in working towards happier, healthier and more satisfying relationships.

Attachment Theory

Attachment theory is a body of work developed by John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth in the 1960s and 70s. Bowlby and Ainsworth revolutionised how people viewed a child’s tie to its’ mother and showed the impact of disruption of a close and loving bond on later mental and emotional health.

The way in which the caregiver responds to the infants’ signals of need, and the way the infant then ends up getting it’s early needs met, creates an internal working model that continues to influence close relationships as adults. The internal model also influences how an adult sees the world more broadly, and how they relate to themselves and their feelings.

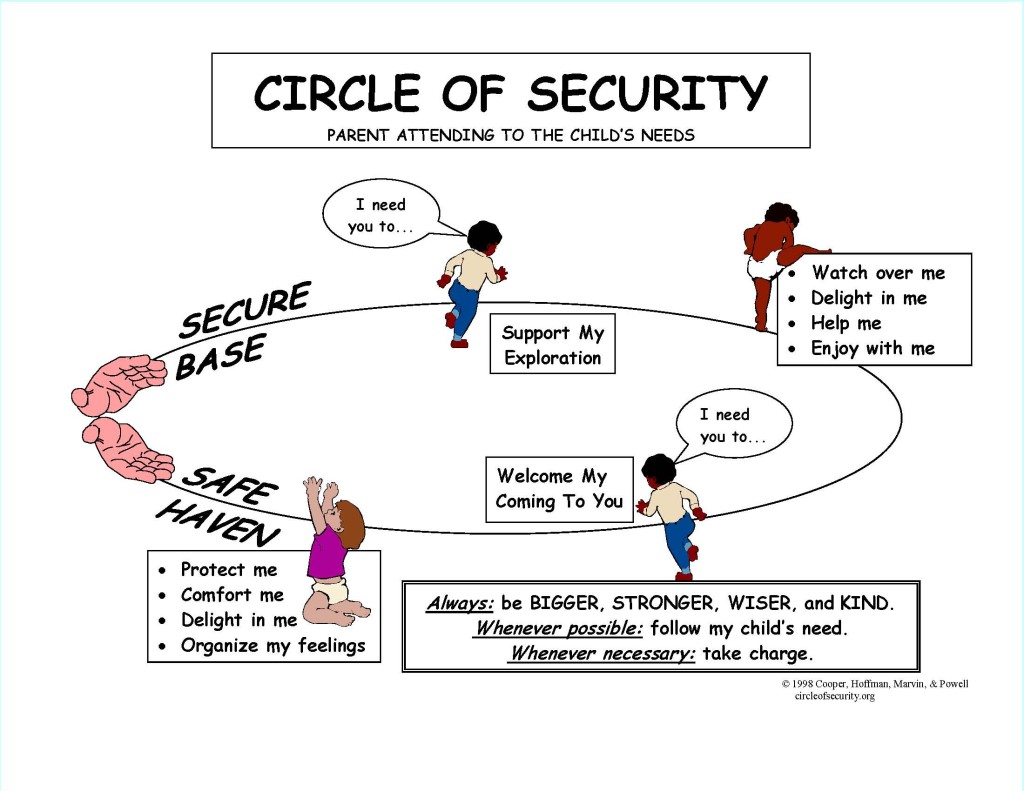

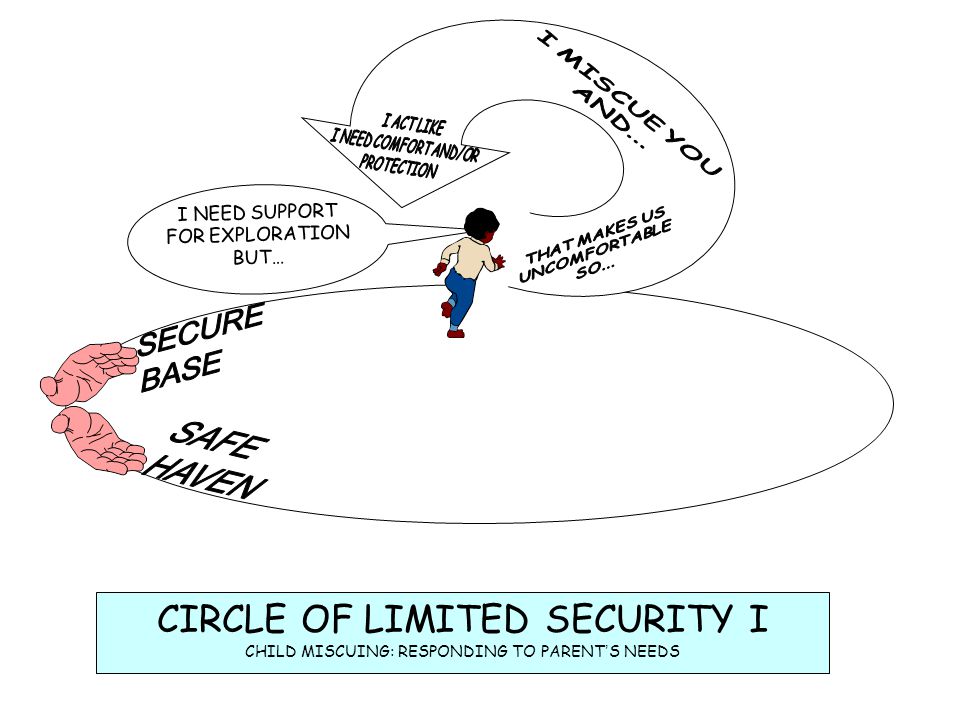

Circle of Security

I originally wrote this article in 2015 after a colleague shared a presentation on the Circle of Security. This body of work aims to help parents develop positive, secure relationships with their young children, and is based in part on attachment theory.

In this article I will refer mainly to the Circle of Security work. I will outline the main attachment styles and will elaborate in each section on the tendencies of each style in adult relationships.

A word about the names of the categories: different researchers have given slightly different names for the styles and it has become complicated! I will include the different terms as we go.

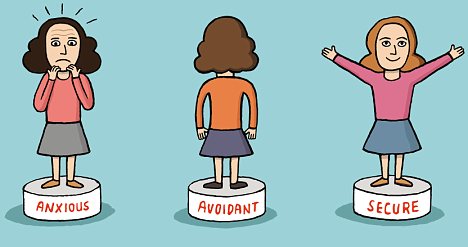

Attachment styles

Consistent and empathic responses from caregivers in their responses to the childs’ need, essentially leads to secure attachment. Anything much less than consistent and empathic, and a child will develop an insecure style, dialing up or down its’ needs depending on what strategy gets its’ needs met more effectively.

According to Mary Main’s work, we can have a primary and a secondary style, and we can also have traits of other styles within a main one.

We tend to only see attachment patterns come out in intimate or very close relationships. Mary Main worked on adult attachment categories further and in her work the adult’s style is called a different name to the child’s style. I will add that in brackets as needed).

Figuring out your attachment style

The quizes available online will give you a sense of your conscious style. In order to get at unconscious patterns, Mary Main developed an Adult Attachment Interview. This is an indepth interview which takes a few weeks to score so is used more for research purposes.

I have trained in offering a modified form of this which gives an impression of your attachment style. Dan Seigel also supports the use of these shorter interviews (he made his own) to make this important work more accessible to regular folks for reasonable fees.

The Modified AAI I have been trained in takes about an hour for the interview and requires a few hours of scoring. The results can then inform our attachment-oriented work together to get you further along the path to earned security! Get in touch to book an interview!

Secure attachment

In secure attachment the parent is the safe, secure base from which the child can go off and explore, and return to as needed. To support secure attachment the parents supports the child’s exploration, and supports their return. The parent is Bigger, Stronger, Wiser and Kind. Read more detail here on travelling around the circle of security.

For example, imagine a 2 yr old close to a parent. The pair are at a playground and the child soon decides to go explore the playground. The parent lets him go and keeps an eye on him. The boy goes off happily and meets another child. Alas the child doesn’t want to share their toy, so the boys’ feelings are hurt. The child comes running back to the parent who offers a hug and says something like “oh, sweety, your feelings are hurt. [hug] The boy didn’t want to share his toy? Oh that’s hard. [Holding close until he settles]. Yes, it makes sense you wanted to use that truck – it’s such a nice yellow one.”

In secure attachment, the parent is available to comfort and provide the child with what he needs emotionally, so the child gets “filled up”, feels safe again, is reassured, and then can go off again into the world. In secure attachment a child learns that they are deserving of love and affection and that it is available for them.

“The child does not need to focus on the needs of the caregiver, but can simply attend to what s/he wants, needs, thinks, and feels and make that known all the way around the Circle.” (source)

An adult with a secure attachment style will typically enjoy a range of healthy relationships:

- Being close with others is fairly easy.

- Being with your own feelings is easy – they are easy to identify and you can be with yourself as the feelings come and go (i.e. good at “self-regulation”)

- It is relatively easy to discern and maintain healthy boundaries between self and other.

- You know when you’re off centre and generally know what to do about it.

- You trust that support will be there

- You trust that things will be okay again during challenging times

Unsurprisingly a very small minority of adults have totally secure attachment styles! We can work towards getting earned security though!

Insecure: Avoidant (aka Dismissing in Adults)

The other kinds of attachment can be seen as ways of avoiding difficulties.

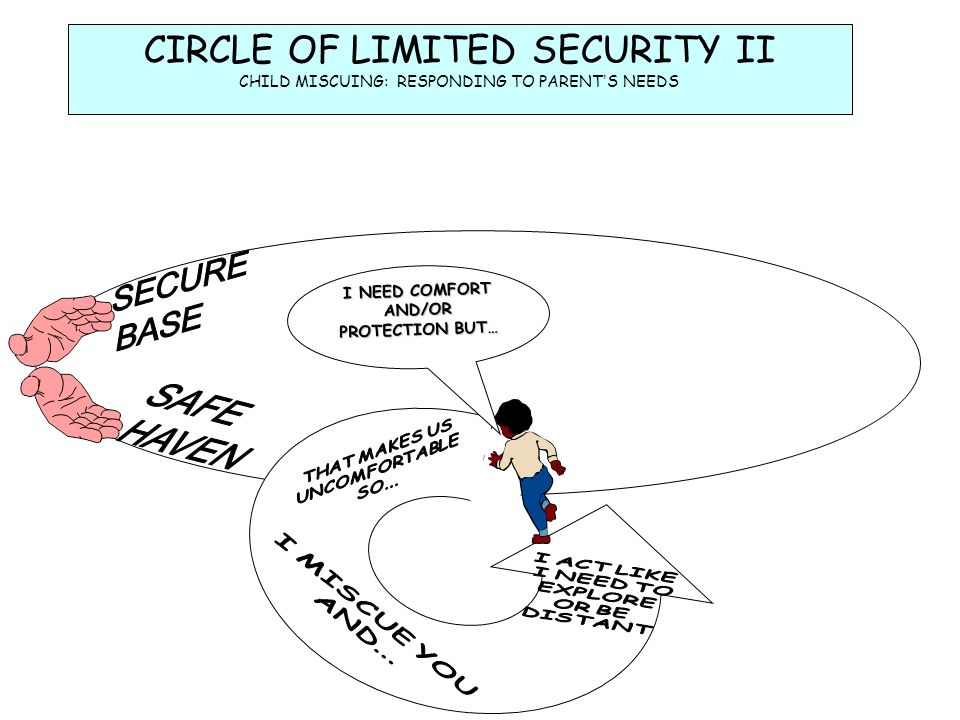

If the parent dismissed the childs concerns as not important (e.g. “oh don’t be silly/a cry baby, just go play somewhere else instead” or “you’ve got it easy, let me tell you about the childhood I had…”). The child learns to ignore and dismiss their feelings. Or if the parent tended to be highly stressed or reactive when the child needed help, seeing the child’s concern as a threat to themselves instead of a call for help. (i.e they regularly get angry if the child is upset) then the child learns that it’s better not to express their needs, ie they avoid their needs.

“Avoidant—an organized strategy of attachment that overemphasizes the exploratory aspects of the relationship (secure base/top half of Circle) while underemphasizing the need for emotional closeness and comfort (safe haven/bottom half of Circle). This strategy allows a child to stay as close as possible to the caregiver while expressing a minimum of emotional need. This attachment strategy is not considered a risk for significant psychopathology.” (source)

As an with an adult with an avoidant/dismissing attachment style:

- will “dial down” his emotions and/or not be able to identify an emotion

- will not easily see or be able to be with other’s emotions because as a child they learnt not to feel emotions

- tend to be more concrete and practically-oriented

- tend to minimise problems and be good at letting things go

- tend to be the “distancer” in the pursuer/distancer dynamic

Insecure: Anxious/Ambivalent (aka Preoccupied in Adults)

“Ambivalent—an organized strategy of attachment that overemphasizes the demonstration of closeness and proximity (safe haven/bottom half of Circle) while underemphasizing the exploratory aspects of the relationship (secure base/top half of Circle). The child seeks to keep an inconsistent caregiver available through a heightened display of emotionality and dependence. This attachment strategy is not considered a risk for significant psychopathology.” (source)

An anxious (or preoccupied) attached adult will tend to:

An anxious (or preoccupied) attached adult will tend to:

- put a lot of focus on staying in connection with a significant other

- this is often seen as a “neediness” and the anxiously attached person will typically become the “pursuer” in the pursuer/distancer dynamic

- tend to need external regulation

- have no trust that they can survive a difficult process

- will tend to feel over-connected during a break-up and experience high anxiety

Insecure: Disorganised Attachment style (aka Unresolved in Adults)

Disorganised attachment is typically a mixture of avoidant and ambivalent tendencies that don’t fall in a regular pattern.

This style often occurs because of the “attachment of a child to a caregiver who is either frightened of the child or frightening to the child (or both); a breakdown in organized behavior by the child when needing to seek comfort and protection from the attachment figure, particularly when under stress. This attachment style is considered to be at risk of significant psychopathology.” (source)

An adult with disorganised attachment:

- will likely have significant problems maintaining relationships

- may feel a “push/pull” inside re relationship – a strong desire for closeness, then a strong fear or anxiety.

- will likely experience more pervasive anxiety in life

- may find themselves in dramatic relationships

- folks with more severely disorganised styles may exhibit Borderline Personality tendencies

The COS also recognises Negative Attachment: “attachment to a “procedural script” regarding how to function within relationship; this script, learned within the context of an insecure or disorganized attachment, allows for a limited experience of connection (“This may be painful, but at least it allows some predictability and some sense of connection.”)(source)

Going forward – the good news

Research indicates attachment style can indeed be changed – we can become more securely attached in adulthood even if we weren’t in childhood. This can be done through working with an attachment-oriented therapist, through understanding and recognising your own patterns and trying new ones, and through being in a relationship with a person who is more securely attached than you. Healing attachment wounds and becoming more securely attached is often a long-term endeavour requiring significant consciousness and effort, but it’s possible.

Here are some of my favourite resources

Attached, by Amir Levine and Rachel Heller

How to be an adult in relationships, by David Richo

Family Ties That Bind, by Ron Richardson

Getting the Love You Want & Keeping The Love You Find, by Harville Hendrix

Adult Children of Alcoholics, by Janet Woititz

Find some very useful videos here for parents, courtesy of Circle of Security International (e.g. “Being With and Shark Music” (i.e. parental reactivity).

If you would like to have me conduct an interview to give you an impression of your attachment style, please find out more here and get in touch with me! Then we can work together towards more security!